ANTAKYA, Turkey: Only 30 minutes from the Syrian border, the ethnically Arab city of Antakya, belies the typical impression of Turkey. The modern city of maybe 40,000 is nothing like the 100,000 inhabitants it accommodated during the Roman and Byzantine eras, when the city was called Antioch. In its glory days, it sheltered Marc Antony and Cleopatra before their defeat by Augustus and subsequent retreat back to Egypt.

Antioch was a vital outpost for the Byzantium empire during the Crusades era, the last major defense from an Arab invasion and later the final defense from the renegade Crusaders, who turned on their Byzantine brethren in religion to quench their thirst for power. Over time, the battles for Antioch eventually led to its destruction, leaving only sporadic ruins of what once was one of the greatest cities of the Eastern Roman and Byzantine Empires. The Ottomans later resurrected the ancient site under the name Antakya.I had recently finished the book The Crusades Through Arab Eyes and as I entered Turkey, I was extremely excited to find myself in the historical city of Antioch. Little did I know that my true fascination with this town would have a contemporary source.

Despite the romantic appeal of its history, Antakya is little more than a forgotten realm on the Turkish-Syrian border. It is as unassuming as any other small town on the planet. Quiet and in need of a bit of cleaning, Antakya, like most southeastern Turkish towns, has a lot of potential for development.

The city is split by a little river that separates most of the residential area from the commercial areas. Although the people are Arab by ethnicity, the architecture is strikingly at odds with its Syrian neighbor despite being only an hour or so away from Aleppo. In a departure from the large apartment complexes popular in Middle Eastern metropolises, houses with pointed roofs line Antakya’s residential area, imparting a European feel to the region. Indeed, looking down from the ruins of ancient Antioch, you might mistake the modern town for a Germanic village among the hills.

Quaint as that sounds, I have to admit it’s not very scenic. However, I made up for the lack of spectacular views, large mountain peaks or valleys with a quick little jaunt into the main commercial area of the town. As I strolled through the city streets lined with numerous cafés and shops, I began hearing people talking in a language that was eerily familiar. I had heard Turkish spoken before by friends in the States, enough to know I was not going to be able to communicate in Turkish anytime soon, much less while in Turkey. This language was something else.

I can communicate in Arabic, as I’ve lived in Egypt and had just spent a few weeks in Syria. With the Syrian border so close, it wasn’t surprising for me to think Arabic might be spoken here. But as I listened closer, I realized that wasn’t it either, though it sounded similar. Not Turkish, not Arabic — I had to find out what this was.

I stopped in a little restaurant for my first meal in Turkey. Around me, the waiters were speaking that strange, yet familiar language. When one of the staff came over and, in pristine Arabic, asked for my order, I couldn’t contain my curiosity any longer. What language was he speaking over with his friends? To my surprise, he told me that it was Aramaic.

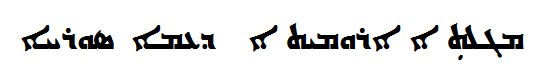

Thought to be a dead language by many in the West, Aramaic was widely spoken in the Holy Land 2,000 years ago, during the time of Jesus Christ. It was gradually replaced by Arabic when the Arabs began to move north from the Arabian Peninsula. Eventually Aramaic became dormant, leaving only pockets of people still speaking the ancient language. Antakya is one of those few locations on the globe that Aramaic remains a spoken and living language.

A combination of Arabic and Hebrew in sound, Aramaic is arguably the most beautiful of the Semitic languages. Soft, but with the traditional vocalizing that Semitic languages contained, Aramaic is easy on the ears.

History has a funny way of asserting itself in the most unsuspecting moments. Here I was, in a town in Turkey I had never even heard of just weeks before, and I had stumbled upon one of the few remaining enclaves of Aramaic. There I was, eating a meal and watching in amazement as the daily routine was carried out in a language I had assumed had vanished long ago. It made me almost shiver to know that I was listening to the language that was spoken by one of the most influential figures in history.

What I had originally viewed as sacred turned out in real life to be quite mundane. I spent one night in a local café watching the most popular Turkish football club play Liverpool. While I sipped my coffee, the conversations around me, I realized, were a mix of Turkish and Aramaic — a combination that brings joy to the ears. As the spectators argued with the announcers and winced as Liverpool scored, I was in heaven as they did so in mostly Aramaic.

Following my brief stop in Antakya, I embarked to learn as much about the history of Aramaic as I could. While it was exciting to read, nothing could be as exciting as experiencing something firsthand.

Months later, I watched The Passion of the Christ, which Mel Gibson scripted and filmed entirely in Aramaic. As I did so, Antakya, its people and shops began to creep into my mind. I wondered what everyone else in the movie theater was thinking at that moment. Did they realize that the language of the film was still alive and actively used in parts of the world? Perhaps not. An enigmatic smile crossed my face as my mind drifted, hearing the same words coming from the silver screen being spoken by a Turkish football fan next to me in a café in Antakya.

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar