söndag 14 februari 2010

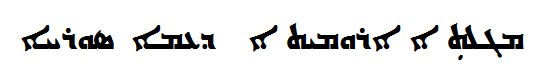

Syriac tablet found at Edessa in Turkey

Turkish Tongue Twisting – a little Aramaic anyone

ANTAKYA, Turkey: Only 30 minutes from the Syrian border, the ethnically Arab city of Antakya, belies the typical impression of Turkey. The modern city of maybe 40,000 is nothing like the 100,000 inhabitants it accommodated during the Roman and Byzantine eras, when the city was called Antioch. In its glory days, it sheltered Marc Antony and Cleopatra before their defeat by Augustus and subsequent retreat back to Egypt.

Antioch was a vital outpost for the Byzantium empire during the Crusades era, the last major defense from an Arab invasion and later the final defense from the renegade Crusaders, who turned on their Byzantine brethren in religion to quench their thirst for power. Over time, the battles for Antioch eventually led to its destruction, leaving only sporadic ruins of what once was one of the greatest cities of the Eastern Roman and Byzantine Empires. The Ottomans later resurrected the ancient site under the name Antakya.I had recently finished the book The Crusades Through Arab Eyes and as I entered Turkey, I was extremely excited to find myself in the historical city of Antioch. Little did I know that my true fascination with this town would have a contemporary source.

Despite the romantic appeal of its history, Antakya is little more than a forgotten realm on the Turkish-Syrian border. It is as unassuming as any other small town on the planet. Quiet and in need of a bit of cleaning, Antakya, like most southeastern Turkish towns, has a lot of potential for development.

The city is split by a little river that separates most of the residential area from the commercial areas. Although the people are Arab by ethnicity, the architecture is strikingly at odds with its Syrian neighbor despite being only an hour or so away from Aleppo. In a departure from the large apartment complexes popular in Middle Eastern metropolises, houses with pointed roofs line Antakya’s residential area, imparting a European feel to the region. Indeed, looking down from the ruins of ancient Antioch, you might mistake the modern town for a Germanic village among the hills.

Quaint as that sounds, I have to admit it’s not very scenic. However, I made up for the lack of spectacular views, large mountain peaks or valleys with a quick little jaunt into the main commercial area of the town. As I strolled through the city streets lined with numerous cafés and shops, I began hearing people talking in a language that was eerily familiar. I had heard Turkish spoken before by friends in the States, enough to know I was not going to be able to communicate in Turkish anytime soon, much less while in Turkey. This language was something else.

I can communicate in Arabic, as I’ve lived in Egypt and had just spent a few weeks in Syria. With the Syrian border so close, it wasn’t surprising for me to think Arabic might be spoken here. But as I listened closer, I realized that wasn’t it either, though it sounded similar. Not Turkish, not Arabic — I had to find out what this was.

I stopped in a little restaurant for my first meal in Turkey. Around me, the waiters were speaking that strange, yet familiar language. When one of the staff came over and, in pristine Arabic, asked for my order, I couldn’t contain my curiosity any longer. What language was he speaking over with his friends? To my surprise, he told me that it was Aramaic.

Thought to be a dead language by many in the West, Aramaic was widely spoken in the Holy Land 2,000 years ago, during the time of Jesus Christ. It was gradually replaced by Arabic when the Arabs began to move north from the Arabian Peninsula. Eventually Aramaic became dormant, leaving only pockets of people still speaking the ancient language. Antakya is one of those few locations on the globe that Aramaic remains a spoken and living language.

A combination of Arabic and Hebrew in sound, Aramaic is arguably the most beautiful of the Semitic languages. Soft, but with the traditional vocalizing that Semitic languages contained, Aramaic is easy on the ears.

History has a funny way of asserting itself in the most unsuspecting moments. Here I was, in a town in Turkey I had never even heard of just weeks before, and I had stumbled upon one of the few remaining enclaves of Aramaic. There I was, eating a meal and watching in amazement as the daily routine was carried out in a language I had assumed had vanished long ago. It made me almost shiver to know that I was listening to the language that was spoken by one of the most influential figures in history.

What I had originally viewed as sacred turned out in real life to be quite mundane. I spent one night in a local café watching the most popular Turkish football club play Liverpool. While I sipped my coffee, the conversations around me, I realized, were a mix of Turkish and Aramaic — a combination that brings joy to the ears. As the spectators argued with the announcers and winced as Liverpool scored, I was in heaven as they did so in mostly Aramaic.

Following my brief stop in Antakya, I embarked to learn as much about the history of Aramaic as I could. While it was exciting to read, nothing could be as exciting as experiencing something firsthand.

Months later, I watched The Passion of the Christ, which Mel Gibson scripted and filmed entirely in Aramaic. As I did so, Antakya, its people and shops began to creep into my mind. I wondered what everyone else in the movie theater was thinking at that moment. Did they realize that the language of the film was still alive and actively used in parts of the world? Perhaps not. An enigmatic smile crossed my face as my mind drifted, hearing the same words coming from the silver screen being spoken by a Turkish football fan next to me in a café in Antakya.

Turkish Finance Minister pledges support for training of Syriac Clergy

Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu pledged to support Syriac efforts to cultivate religious leaders to help sustain their culture, religion and language during a meeting over the weekend with community leaders in Mardin.

The Mardin and Diyarbakır archbishop, contacted by the Hürriyet Daily News & Economic Review after his meeting with the foreign minister, said education remains the biggest problem facing the Syriac community in Turkey.

“We spoke with the minister. There is an overwhelming need to raise religious leaders with comprehensive knowledge of the language, culture and religion for the Syriac community and the Syriac churches,” Archbishop Saliba Özmen told the Daily News in a telephone interview Monday.

“The foreign minister has approached our needs positively. I am optimistic that we’ll resolve our problems together,” he said.

Mardin, known for its strategic location on a rocky mountain overlooking the plains of Syria, contains a mixed population of Turks, Kurds, Syriacs and Arabs, as well as a small Armenian community. While in the border city with a group of ambassadors, Davutoğlu described Mardin as “kadim,” which means the one with an eternal tradition.

One of Davutoğlu’s primary stops in Mardin was the 1,500-year-old Syriac Deyrülzafaran Monastery. The foreign minister toured the ancient building with the archbishop, who recounted the monastery’s history and informed Davutoğlu about the problems of the community, whose members have decreased over the years for several reasons.

“The first thing that comes to mind when Mardin is mentioned are the Syriacs. We have a 5,500-year-old history in this land, but we are on the verge of becoming extinct,” said Özmen. “Most of the churches, monasteries and villages had been evacuated or destroyed. In the past, there were many churches in the region extending from Diyarbakır to Silopi and Cizre in southeastern Anatolia, but now there are only six or seven active churches.”

The population of the Syriac community has declined from 200,000 to 3,000. Those remaining are densely concentrated in Mardin and the surrounding areas, including Midyat. According to Özmen, many have had to immigrate for economic, social and political reasons.

“Nobody was forced to leave their homeland without a compelling reason. There was a big flow to Syria throughout the late 1930s,” the archbishop said. “After the 1960s, Syriac immigration to Sweden and Germany, and even to the U.S. and Australia, began. In the late 1980s, there were security-related problems that left the Syriac community in a dilemma. Most of them had to leave their land.”

The Syriac church had a patriarchate in Turkey until the 1930s, when it had to move to Syria. The archbishops of all Syriac churches now meet in Damascus. The problem in the 1980s was related to terrorism and Turkey’s boosting of security measures in the southeast in its fight against the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK.

“But there have been good steps taken in recent times. We can practice our religion,” said Özmen. “What matters is keeping this deep-rooted heritage and culture alive. The problems can be easily overcome if we, as the citizens of Turkey, approach them with mutual goodwill. To my view, regardless of his religion, language and culture, everyone should enjoy broader liberties. This diversity is Turkey’s richness, which will take us to the true path.”

The Mor Gabriel Monastery, Mor Yakup Monastery, Virgin Mary Monastery and Mor Abraham Monastery are among the religious places in Mardin and its surrounding area. Mor means “saint” in the Syriac language.

Syriacs worshipped the sun before converting to Christianity.

lördag 13 februari 2010

Turkey's Homework on Minority Rights

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (ACPE) passed a document on 27 January regarding measures to be taken by Turkey in the context of minority rights. The ACPE expects a progress report related to the measures from Turkey until February 2011.

Religious Clergy: Turkey should find constructive solutions concerning the training of religious minorities' clergy and the granting of work permits for foreign members of the clergy.

Legal personality of religious institutions: The state should recognize the legal personality of the Ecumenical Orthodox Patriarchate in Istanbul, the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, the Armenian Catholic Archbishopric of Istanbul, the Bulgarian Orthodox Community within the structures of the Ecumenical Orthodox Patriarchate, the Chief Rabbinate, and the Vicariate Apostolic of Istanbul. The absence of legal personality which affects all the communities concerned has direct effects in terms of ownership rights and property management.

Theological college: The Country should find an agreed solution with the representatives of the minority with a view to the reopening of the Heybeliada Greek Orthodox theological college (the Halki seminary), inter alia by making official in writing the proposal to reopen the seminary as a department of the Faculty of Theology of Galatasaray University, in order to open genuine negotiations on this proposal.

Ecumenical title: the Ecumenical Orthodox Patriarchate in Istanbul should be given the freedom to choose to use the adjective "ecumenical".

Places of worship and foundations: Turkey should resolve the question of the registration of places of worship and the question of the mazbut ('registered') properties confiscated since 1974, which must be returned to their owners or to the entitled persons or, where the return of the assets is impossible, to provide for fair compensation.

Mor Gabriel: the Orthodox Syriac monastery of Mor Gabriel, one of the oldest Christian monasteries in the world, founded in 397 AD should be ensured to not be deprived of its lands, and that to be protected in its entirety. The Assembly expresses equal concern about the current status of the unlawful appropriation of significant amounts of land historically and legally belonging to a multitude of other ancient Syriac monasteries, churches and proprietors in south-east Turkey.

Syriac people: Turkey should recognize, promote and protect the Syriac people as a minority. This shall include, but shall not be limited to, officially developing their education and carrying out religious services in their Aramaic native language.

Public services: The state should take practical measures to make possible for members of national minorities admission to police forces, the army, the judiciary and the administration.

Violence against minorities: Turkey should firmly condemn all violence against members of religious minorities (whether they are Turkish citizens or not), and conduct effective investigations and promptly prosecute persons responsible for violence or threats against members of religious minorities, particularly in respect of the murders of an Italian Catholic priest in 2006 and three Protestants in Malatya in April 2007.

Hrant Dink murder: The legal proceedings concerning the murder of Hrant Dink in 2007 should be completed. The Assembly particularly invites the Turkish Parliament to follow up without delay the report of its sub-committee responsible for investigating the murder of Hrant Dink, a report which has highlighted errors and negligence on the part of the security forces and the national police, without which this murder could have been prevented.

Circular: The circular on the freedom of religion of non-Muslim Turkish citizens, issued by the Ministry of the Interior on 19 June 2007, should be implemented, and its impact should be evaluated.

Cemeteries: Turkey should fully implement Law No. 3998, which provides that cemeteries belonging to minority communities cannot be handed over to municipalities, and thus to prevent the building of housing which has been observed on certain Jewish cemeteries.

Desecration of sacred space: The country should address seriously the problem of the desecration of the Catholic cemetery in the Edirne-Karaagac quarter, which is a sacred burial place for Polish, Bulgarian, Italian and French Catholics, and facilitate the restoration of the destroyed memorials and sepulchers there.

Education: Legislation should be adapted so as to allow children from non-Muslim minorities, but without Turkish nationality, to be admitted to minority schools.

Gökçeada and Bozcaada islands: The bicultural character of the two Turkish islands Gökçeada (Imbros) and Bozcaada (Tenedos) should be preserved as a model for co-operation between Turkey and Greece in the interest of the people concerned.

Ombudsman: The office of ombudsman (pending since 2006) should be instituted, as this will be of key importance in avoiding tension in society.

Hate speech: Anti-Semitic statements and other hate speech, including any form of incitement to violence against members of religious minorities, should be made criminal offences.

Media: Turkey should encourage the development by the media of a code of ethics on respect for religious minorities, bearing in mind the vital role that they can play in the perception of these minorities by the majority.

Campaign against racism: A national campaign against racism and intolerance should be organized, stressing that diversity is to be regarded not as a threat but as a source of enrichment. (TK/VK)

Source: ACPE